2018 – The Barometer Begins to Fall

2018 – The Barometer Begins to Fall

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) went into effect on May 25, 2018, and introduced privacy concepts that were new to some U.S. businesses. Fortunately, the GDPR was developed over a period of time that allowed for thoughtful deliberation and careful drafting.

The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), on the other hand, was speedily enacted under the threat of a ballot initiative. As a result, consumers and businesses alike have expressed concerns with many of the provisions and the legislature, to its credit, has attempted to correct some of those issues. Proposed regulations issued by the California Attorney General’s Office provide some clarity, but the consensus is that they fall short of the expectations of businesses.

2019 – Rigging for Rough Seas

The privacy concepts of the GDPR and CCPA include the requirement of consent, the right to access, correct and delete personal information, transparency through privacy policies, and data security and minimization. These concepts struck a chord with many, and a number of states introduced, but did not enact as of this date, legislation similar to or having elements in common with the CCPA. Those states include Hawaii (SB 418), Massachusetts (SB 120), New York (SB 4411/AB 6351 and AB 7736), Pennsylvania (HB 1049), Rhode Island (SB 234/HB 5930), Texas (HB 4518) and Washington (SB 5376/HB 1854).

To their credit, some states, described below, chose to look before leaping and formed task forces or workgroups to develop recommendations.

Legislation regarding data breach notifications was also a hot item in 2019 with a number of states expanding definitional coverage or decreasing the number of persons required to be affected before notification to government authorities, among other things.

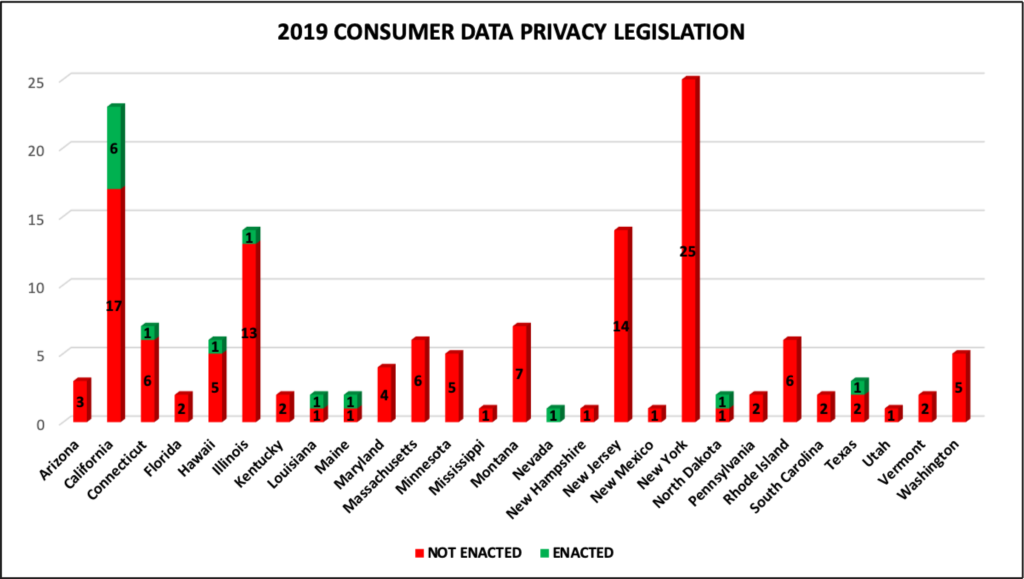

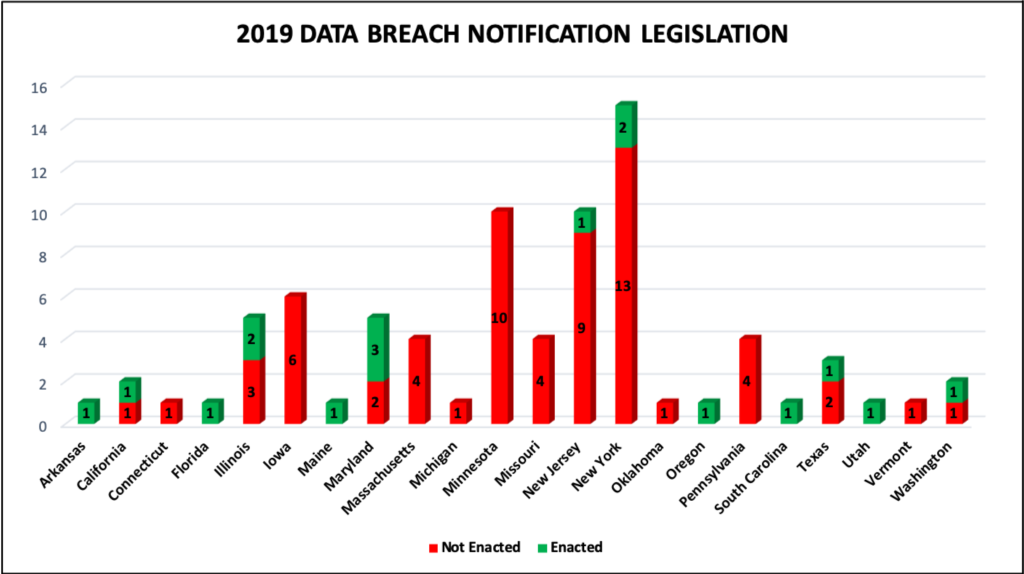

The following charts depict the outcome of consumer data privacy legislation (approximately 149 bills introduced and 14 enacted) and data breach notification legislation (approximately 80 bills introduced and 17 enacted) in 2019.[1] Importantly, some of the legislation “not enacted” will carry over to 2020, and several state legislatures are still in session.

Below are brief summaries of data privacy and data breach legislation enacted in 2019, excluding those affecting only government entities.

Arkansas

HB 1943 amends the Personal Information Act by expanding the definition of “personal information” to include biometric data. The law also requires that in the event of a data breach that requires notification to more than 1,000 affected persons, the Attorney General must also be notified. The law became effective July 23, 2019.

California

AB 25, AB 874, AB 1146, AB 1355 and AB 1564 amend the CCPA in a number of ways, including:

- Exempting from most provisions of the CCPA, until Jan. 1, 2021, personal information collected relating to employment.

- Clarifying that “personal information” does not include “deidentified or aggregate consumer information” or publicly available information obtained from government records.

- Providing there is no right to deletion with respect to vehicle and ownership information shared between the manufacturer and dealer when it is necessary to “fulfill the terms of a written warranty or product recall conducted in accordance with federal law.”

- Allowing differential treatment of consumers provided it is “reasonably related to [the] value provided to the consumer by the consumer’s data.”

- Allowing a business that operates exclusively online to provide consumers only with an email address for submitting requests for information.

The effective date of these amendments is Jan. 1, 2020.

AB 1130 amends the Information Practices Act by expanding the definition of “personal information” to include, in combination with an individual’s first name or first initial and last name, a tax identification number, passport number, military identification number, other unique identification number issued on a government document, and unique biometric data.

Additionally, if the data breach involves biometric data, the notification may include “instructions on how to notify other entities that used the same type of biometric data as an authenticator to no longer rely on data for authentication purposes.” The effective date is Jan. 1, 2020.

AB 1202 requires data brokers register with the Attorney General. The effective date is Jan. 1, 2020.

Connecticut

SB 1108 establishes “a task force to study the interests consumers have in protecting their privacy and possible methods to achieve such protection in this state while not overly burdening the businesses in this state.” Regarding methods, the task force is specifically directed to examine the CCPA. The task force is required to submit its findings and recommendations to the legislature by Jan. 1, 2020.

Hawaii

HCR 225 creates a “twenty-first century privacy law task force . . . to examine and recommend laws and regulations relating to internet privacy; the collection, transmission, processing, protection, storage, and sale of personal data; hacking; data breaches; and other similar subjects.” The concurrent resolution requires the task force to submit its findings and recommendations to the legislature by Dec. 1, 2019.

Illinois

HB 2189 amends the Genetic Information Privacy Act by prohibiting a “company providing direct-to-consumer commercial genetic testing [] from sharing any genetic test information or other personally identifiable information about a consumer with any health or life insurance company without written consent from the consumer.” The effective date is Jan. 1, 2020.

SB 1624 amends the Personal Information Protection Act by requiring that any data collector who must inform more than 500 Illinois residents of a data breach also provide notice to the Attorney General describing:

- the nature of the breach;

- the number of affected residents; and

- any steps taken or intended to be taken.

The notice must be provided “in the most expedient time possible and without unreasonable delay but in no event later than when the data collector provides notice to consumers pursuant to this Section.” The effective date is Jan. 1, 2020.

Louisiana

HR 249 “urge[s] and request[s] the Southern University Law Center to establish a task force to study the effects of the sale of consumer personal information by internet access service providers, social media companies, search engines, or other websites and providers of online services that may collect and sell consumer personal information, and submit its findings in the form of a written report to the House Committee on Commerce no later than sixty days before the 2020 Regular Session of the Legislature,” Jan. 30, 2020.

Maine

SP 275 (LD 946) prohibits a provider of broadband internet access services from using, disclosing, selling or permitting access to customers’ personal information without consent, subject to certain exceptions. The effective date is July 1, 2020.

Maryland

HB 1154 and SB 693 amend the Personal Information Protection Act by distinguishing businesses that maintain computerized data from those that own or license the data, and prohibits the former from charging the latter a fee for providing information needed to make notification of a breach. The law also restricts an owner’s/licensee’s use of information relative to a breach. The effective date was Oct. 1, 2019.

SB 30 specifies how insurance carriers must notify the Insurance Commissioner in the event of a data breach. The effective date was Oct. 1, 2019.

Nevada

SB 220 went into effect Oct. 1, 2019, and has aspects similar to the CCPA. While the law does not provide consumers with a right to know, it does provide them a right to request the operator of a website or online service not to sell their covered information. Operators must have a “designated request address” which can be an email address, toll-free telephone number or website.

The term “sale” does not include: “1) The disclosure of covered information by an operator to a person who processes the covered information on behalf of the operator; 2) The disclosure of covered information by an operator to a person with whom the consumer has a direct relationship for the purposes of providing a product or service requested by the consumer; 3) The disclosure of covered information by an operator to a person for purposes which are consistent with the reasonable expectations of a consumer considering the context in which the consumer provided the covered information to the operator; 4) The disclosure of covered information to a person who is an affiliate [] of the operator; or 5) The disclosure or transfer of covered information to a person as an asset that is part of a merger, acquisition, bankruptcy or other transaction in which the person assumes control of all or part of the assets of the operator.”

The law does not apply to entities “subject to the provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996” or automobile manufacturers and servicers that collect covered information retrieved that is: “(1) Retrieved from a motor vehicle in connection with a technology or service related to the motor vehicle; or (2) Provided by a consumer in connection with a subscription or registration for a technology or service related to the motor vehicle.”

Notably, the law is also inapplicable to any “financial institution or an affiliate of a financial institution that is subject to the provisions of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.” This is broader than the CCPA which only exempts “personal information collected, processed, sold, or disclosed pursuant to the federal Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.”

New Jersey

SB 52 amends the existing data breach notification requirements by providing that the breach involves a username or password in combination with a password or security question answer that would allow access; the business can provide the breach notification in electronic form. The effective date was Sept. 1, 2019.

New York

AB 2374 requires any credit reporting agency that suffers a breach that includes Social Security numbers to offer reasonable identity theft prevention services and mitigation services to consumers at no charge for up to five years. The law became effective Sept. 23, 2019, but applies to credit reporting agency breaches “that occurred no more than three years prior to the effective date of this act.”

SB 5575, the Shield Act (Stop Hacks and Improve Electronic Data Security Act), amends the existing data breach notification law. The law expands “private information” to include the following elements in combination with personal information: 1) account, credit or debit number if the account could be accessed without additional information; 2) biometric information. It additionally includes email addresses or usernames in combination with a password or security question and answer that would permit account access.

Importantly, the law deletes the qualifier “conducts business in New York state” from the description of who must provide breach notifications, so it now applies to “any person or business which owns or licenses computerized data which includes private information [of a resident of New York].” These provisions became effective Oct. 23, 2019.

Notification is not required if it is reasonably determine[d] such exposure will not likely result in misuse of such information, or financial harm,” or if notification is provided in compliance with GLBA, HIPAA or other specific federal or New York statutes, rules or regulations.

The law also provides that a person or business is in compliance if they are a “compliant regulated entity” with respect to the GLBA, HIPAA and other specific federal or New York statutes, rules or regulations. Compliance can also be demonstrated if the data security program includes a laundry list of administrative, technical and physical safeguards. These provisions become effective March 21, 2020.

North Dakota

HB 1485 requires that “the legislative management shall study protections, enforcement, and remedies regarding the disclosure of consumers’ personal data. The study must include a review of privacy laws of other states and applicable federal law. The legislative management shall report its findings and recommendations, together with any legislation required to implement the recommendations, to the sixty-seventh legislative assembly.”

Oregon

SB 684 amends existing data breach law by distinguishing “covered entities” from “vendors,” and defining the latter as “a person with which a covered entity contracts to maintain, store, manage, process or otherwise access personal information for the purpose of, or in connection with, providing services to or on behalf of the covered entity.”

The law requires that a vendor notify a covered entity of a breach “as soon as practicable” but no later than 10 days afterward and to notify the Attorney General if the breach involved more than 250 persons or an undeterminable number of persons. Notably, the law excludes from the notification requirements covered entities and vendors that are subject to and comply with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The effective date is Jan. 1, 2020.

Texas

HB 4390 amends the notification requirements of Texas’ data breach law and creates an advisory council to study data privacy laws generally. The effective date is Jan. 1, 2020.

Currently, a person conducting business in Texas who “owns or licenses computerized data that includes sensitive data” must disclose the breach to any affected individual “as quickly as possible.” Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 521.053(b). The amendments will require the disclosure “be made without unreasonable delay and in each case not later than the 60th day after the date on which the person determines that the breach occurred,” unless instructed otherwise by law enforcement.

Additionally, if the breach involves at least 200 Texas residents, the Attorney General must receive notification within the same timeframe that describes: 1) the nature and circumstances of the breach; 2) the number of residents affected; 3) the measures taken prior to notification; 4) the measures intended to be taken following notification; and 5) law enforcement involvement, if any.

Utah

SB 193 amended the Protection of Personal Information Act by excluding from its application “financial institutions” as defined in the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, 15 U.S.C. § 6809(3), and allows for “no greater than $100,000 in the aggregate for related violations concerning more than one consumer” unless the consumer agrees to settle for a larger amount or the violations concern 10,000 or more consumers who are residents of Utah and 10,000 or more consumers who are residents of other states. The law became effective May 14, 2019.

Washington

HB 1071 amends existing data breach law by expanding the definition of “personal information” to include the following data elements, in combination with an individual’s first name or first initial and last name:

- Full date of birth;

- Private key that is unique to an individual and that is used to authenticate or sign an electronic record;

- Student, military, or passport identification number;

- Health insurance policy number or health insurance identification number;

- Any information about a consumer’s medical history or mental or physical condition or about a health care professional’s medical diagnosis or treatment of the consumer; or

- Biometric data generated by automatic measurements of an individual’s biological characteristics such as a fingerprint, voiceprint, eye retinas, irises, or other unique biological patterns or characteristics that is used to identify a specific individual.

The law allows for notice of a data breach to be provided electronically if it involves personal information including a username or password. Additionally, the law decreases the time for reporting a breach to the Attorney General from 45 to 30 days and expands the amount of information required in the notice. The effective date is March 1, 2020.

2020 – The Perfect Storm or Smooth Sailing?

Given the number of bills introduced in 2019, it’s likely that the trend will continue in 2020 which, in the worst-case scenario, would result in a myriad of state privacy laws across the nation. In other words, a compliance bomb cyclone. Will there be a federal solution?

A number of privacy bills have been introduced in Congress, with the most recent also being the most comprehensive, S. 2968 (text), the “Consumer Online Privacy Rights Act” or “COPRA.” The bill has a number of similarities to the CCPA and likewise includes privacy legislation concepts such as the right to access, correct and delete personal information, transparency through privacy policies, and data security and minimization. Unfortunately, in the opinion of many, the legislation would only preempt state laws that are in direct conflict while allowing those that provide a greater level of protection.

“After a while you learn that privacy is something you can sell, but you can’t buy it back.” Bob Dylan, Chronicles, Volume One (2004).

[1] Based on independent research and information published by the National Conference of State Legislatures at http://www.ncsl.org/research/telecommunications-and-information-technology/consumer-data-privacy.aspx and http://www.ncsl.org/research/telecommunications-and-information-technology/2019-security-breach-legislation.aspx.